Team pilot Ruth Churchill Dower recounts a high altitude incident in the Himalaya. A sudden updraught led to a stall and cascade. Despite having two reserve parachutes, Ruth lost 1000ft trying to fix the wing and landed in a tailslide on a precipitous ridgetop perch, luckily mostly unscathed. It makes a cracking story, and there's a good deal to learn about managing mayhem and your personal reserve deployment throwing height.

^ Read the LARGE SCREEN PDF VERSION of this article

"The Bad News: Looks like I’m out of the Paragliding World Cup India 2015 after crash landing on top of a mountain yesterday following a completely recoverable incident of wing folding, but one in which I ran out of space and skill to complete the unfold manoeuvres. Note to Self: must practice more with bed sheets on a windy day.

The Good News: I’m okay and, miraculously, managed to land backwards into the only soily bowl at the foot of a tree on a precipitous ledge of a mountain spur, with sheer drops into the abyss either side of me. Nothing like giving the mountain rescuers a bit of a challenge!"

So, what happened?

On launch, the strong easterly wind was gradually giving way to a light westerly, and conditions looked good with a relatively high cloudbase for Billing. The increase of snow on the back mountains suggested a decrease in temperatures at base, and the possibility of stronger thermals with the colder airmass. However, thermals were punchy in places but weak and scratchy in others after a night of thunderous rain 48 hours prior to this, our first PWC task.

Positioned well out of the start gate, this was possibly one of my best PWC starts yet and I was determined not to lose time, so I flew to the first turnpoint on full speed bar, pulleys overlapping, whooping us all on as we went.

The rough conditions were felt more in between the thermal bullets, but you can ride this on an Icepeak 7 – it’s got such a solid leading edge. I was using my thermal averager on the Oudie to tell me which bits of rising air to ride straight through and which ones to stop and turn in, and I managed to stay with lots of Enzos and Booms, despite having a worse glide angle. They were having to turn more widely so I had the advantage of being able to bank up and get high quickly when I was below them.

I got up to 3,200m after the first turnpoint and set off on glide to the second, heading across the higher spurs where pilots were generally staying high, rather than pushing further out onto the lower spurs where pilots were getting low and having to stop and climb more often.

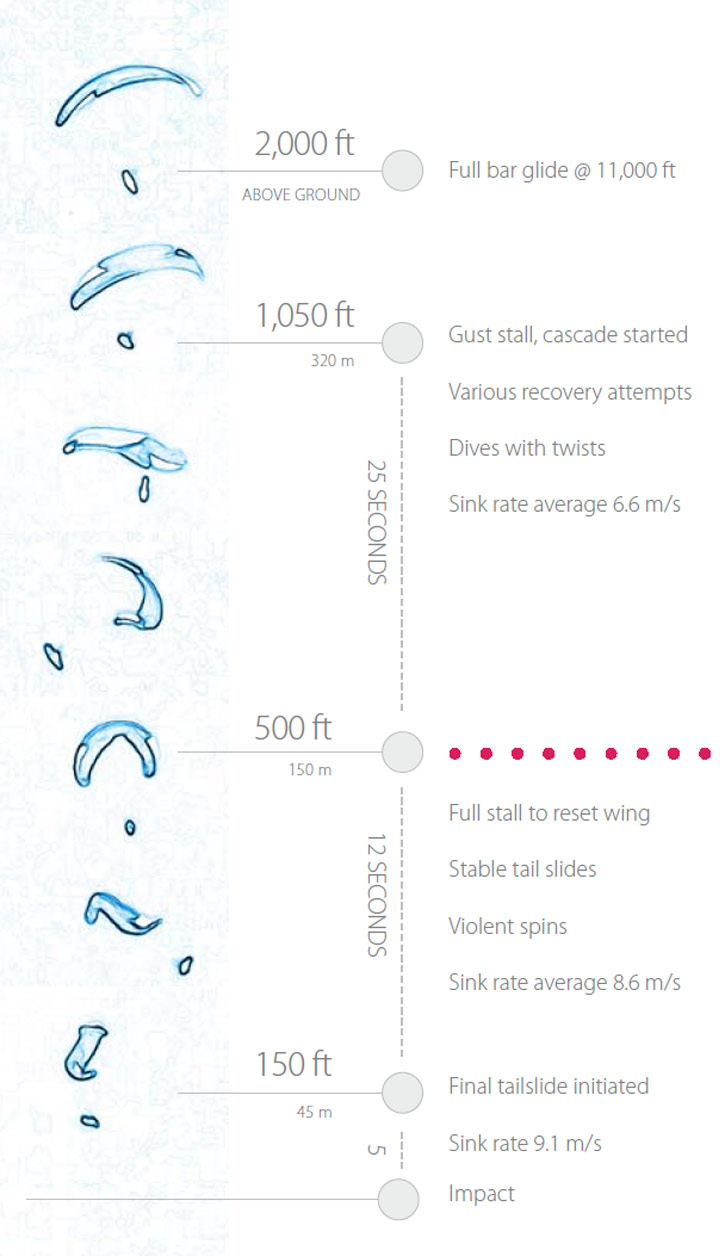

One gaggle ahead had found a strong core on top of a high spur and I headed towards it but got hit on full bar with an intense updraught that caused a gust stall.

.jpg)

I went weightless, then the wing came back fast and hard. There was a lot of non-flying wing in front of me.

The resultant dive and rotation of the slightly open right wing was intense but I managed to stop it after getting two twists and got the collapsed side open as I untwisted. But I still had my legs out straight, resulting in fast twisting and having to think carefully about ensuing brake actions on the opposite side. I think I inadvertently stalled the open wing by holding the deep brake just a milli-second too long.

Each time I thought I had it under control, I was mistaken. The wing was full of energy and with every untwist and counter brake, the other side would collapse causing an aggressive dive, rotation and twist. I had to stop the cascade before the G-Forces went beyond my limit. So I stalled it which had worked a treat in my SIV training to get the wing flying again.

However, this was the Himalayas and I was at high altitude. As I let up from tailslide, the wing went ballistic again, rotating to the left and twisting the risers in the process. I pulled it back into tailslide, legs still flying everywhere, and got it stable again.

I let up once more, and once again, the wing snatched the air into a seriously aggressive rotation and dive – again to the left – so I took it back into tailslide, my position of relative safety at that point. I took a breath, ready to let up as symmetrically as possible, having looked down and realised this was my last chance. But in milliseconds, the chance to fly again was gone.

I looked at both of my reserve handles but it was too late to let go of the wing now. The ground was rushing up towards me, and I knew that if I let up now and did so asymmetrically, I would be thrown against the rocks with a speed that would result in a little facial re-arrangement. Not being quite ready yet for a nip-and-tuck on the old wrinkles, I decided to hold the tailslide in to the ground, thinking it would probably be not too dissimilar to landing under my reserve.

.jpg)

And so, I reversed my way into a neat little soil patch under a tree and sat there trying to get my head around the suddenness of the stop from the previous violent motions that should have really rendered my body somewhat more shattered than it appeared to be.

This was definitely a transition moment in life – what people might call a close call. I wondered, a close call to what?

There’s something indescribably final in those last few moments, when the ground rushes past you faster than you’ve ever seen before and you know you’re going to hit, you don’t know which way up or where, you just know that it will hurt, probably a lot. But even though you know there’s nothing more you can do, you don’t for one minute give up. Well, I didn’t anyway. It wasn’t my time yet. I had a PWC to fly!

I listened to another pilot reporting my crash and wondered how long was it appropriate to just sit and take a moment before trying to find my radio and respond that I was OK. Then my wing rustled to let me know that I wasn’t yet secure on this precipice.

I tried to quickly unclip and get out of my harness to ensure I wasn’t lifted up and away once again. I got a little anxious as the wing started to pull and I couldn’t get the buckles undone, fumbling each attempt in my ski-mitts with rather numb fingers, having fought the strength of the glider all the way down.

Eventually, I was out and sitting on the ground under my wing, looking up and realising it was probably too caught up in the branches above to fly again anyway. So I radioed in my co-ordinates and started the job of making myself and my gear as secure as possible.

All I wanted to do was lie down and, with my wilderness first aid training, I knew it was a good idea to stay as still as possible especially with the increasing neck and back pain.

My knee was hurting a little but seemed unbroken, then it gave way underneath me and released a searing pain. It felt like the lower part of my leg went one way whilst the upper part went the other. Rats. It felt dislocated and I’d already got one rubbish knee. Double rats.

It turned out to be a damaged ligament and meniscus cartilage requiring a leg brace for the travel home (and surgery later) and a micro-fracture of the back. Not even one compressed vertebra! I was lucky.

Flight review

In reviewing the flight track on SeeYou, it turns out that that wing wasn’t really flying at any stage after the collapse, so I was probably in stall – cascade – stall – cascade mode. I fell from 3,100m to 2,810m, so a lot happened in those 300 metres and yet it was still not enough time for me to recover the wing with the skills I had. I hope it would have been plenty of time for someone else perhaps stronger and more accustomed to high speed stall recovery – I really shouldn’t have had to stall it three times.

.jpg)

Some mistakes:

• Not anticipating and stopping the initial collapse.

• Not bending legs underneath to reduce the yaw and twists – this would have made it easier for me to ensure a symmetrical stall recovery without my body yawing all over the place plus it would also have meant that the speed bar was fully off. This may have contributed to the fast left rotations and the reason for the knee injury which didn’t get hit on landing.

• Not leaning my body back into the harness to ensure a clean and symmetrical stall recovery the first time.

• Not keeping an eye on the ground to watch the speed of descent and giving myself the option of pulling my reserve.

I have to stress that I was extremely lucky to land where I did and anyone in a similar situation should really consider using their reserve sooner than I did to ensure a slower landing, especially around rocks.

I came down almost directly on my bum, although must have been slightly leaning to the left judging by the pain, and was hugely grateful for the protection of the airbag and 12cm back protection in my Woody Valley GTO X-Alps harness. Amazing not to have had even one compressed vertebra at that speed.

Funniest moment:

The very wonderful Dr Raj instructing his mountain rescue team on how to lift me onto the body board safely, then said, ‘OK, now that we have her on the board, on my command, all together, we are going to strip her.’ Pause. Head shaking. ‘Er… I mean strap her’. Hysterical.

Scariest moment:

Being carried down the mountain by four wiry young Indian chaps, strapped only to the board with loose climbing ropes (due to pain in back and neck), and having to hold on for dear life as each man stumbled on the precipice and showed me the fast route down (if I fancied some rock surfing). Way more scary than paragliding.

And finally…

My thanks go out to everyone who co-ordinated the rescue on my behalf, including:

• Ulric and Debu who did everything within their power (and some things in their super-powers) to get the chopper to me as fast as possible;

• Ruth J, who kept me sane on the mountain with her best and worst jokes over the radio as we waited, and waited for the chopper (which lost me for a couple of hours and then was unable to approach amidst throngs of free-flyers) whilst I became increasingly cold and shaky;

• The local mountain dwellers further down who lit a fire from their village to show the chopper where I was;

• Dr Raj and his team of mountain climbers who got me off the mountain without any rock surfing;

• The chopper pilot who couldn’t fit the body board in his chopper but determinedly strapped me down to the floor leaving my lower legs and feet hanging out of the side of the chopper as it flew down;

• The pilots who overflew me and radioed my position

• The numerous local support guys who co-ordinated the logistics on the ground;

• Frank S, who runs our ‘boutique’ villa (www.the4roomshotel.com) and keeps us thoroughly entertained day and night, and finally

• My boys (and girl) in the house who rallied round for food, books and phones and made jokes at my expense to aid my recovery. I love you all.

‘OK, now that we have her on the board, on my command, all together, we are going to strip her.’ Pause. Head shaking. ‘Er… I mean strap her’.

Analysis by Greg Hamerton

How does a good pilot with current SIV training and two reserves, end up stalling to the ground? It’s a big warning for all of us with SIV training. The thought: “I’ve got this, I can fix it!” can compromise your safety.

Fixing what is thrashing in your face takes your attention away from an awareness of your height above the ground.

Although those without SIV training might have immediately thrown their reserves in Ruth’s position (and thus been safer), it’s also likely that such pilots will deploy reserves in many more ‘fixable’ situations in which some intelligent piloting input would result in a safer outcome. Applying your SIV training is good, but it must be framed with a strict throwing height limit.

It’s very important to decide what your throwing height is, and to continually monitor your height against this limit during collapse recovery scenarios.

I set mine at 500ft (150m) above the ground: the minimum I would recommend for a clean deployment.

I also practice judging this height while I’m flying, so I’m always aware of the risk if I’m flying in the red zone.

There’s a lot to do during a deployment

You need to look for the handle, grab the handle, pull the handle, look to find a clear space, throw the reserve, look to see it opens, maybe tug on the bridle, then disable the main wing, allow the downplane effect to be reduced, and adopt the PLF position for landing.

At high altitude, sink rates are higher, so this 500ft is used up very fast. If I haven’t fixed a situation by the time I reach this cut-off height, I throw.

What if you’re lower when the wing folds up?

Throw instantly. Even if the reserve only gets rid of your horizontal momentum, it has done something useful, and it can do that when deployed from tree top height.

What if you don’t want to let go of the wing?

It only takes an instant to grab the handle and toss, so I’d recommend getting the reserve out regardless. As soon as the reserve is out, you will stall the wing anyway, to prevent downplaning.

If you’re strong, you can pass the brakes into one hand and maintain a stall while deploying, but it can be tough. This will prevent the wing diving and accelerating, but it will slow down the deployment due to lack of airspeed. Whether it has any benefit depends on your situation.

If you’re extremely low, your reserve has failed, or you’ve failed to deploy, then landing in a stall is a possible option, but it’s likely to be a very hard landing. Get your legs down for a Parachute Landing Fall!

A big thanks to Ruth for sharing this story.

In summary, what happened?

What should you do?

As wing comes forward, release speedbar, pull legs under seat, sit back as symmetrically as possible.

Catch the dives with quick deep brakes, but follow the wing around and exit spirals gradually.

If stalled, release brakes together rapidly when wing overhead.

Check ground clearance. If less than 500 feet above terrain, pull your reserve.