When designers create a harness, they try to match the harness features with the intended use. Each design has a different mix of back protection, buckle style, reserve parachute integration, flight deck options, stowage space and comfort factors like the seat board, straps, and fabric used. Understanding what features you need on your harness can help you narrow down your search.

(a) Back protection

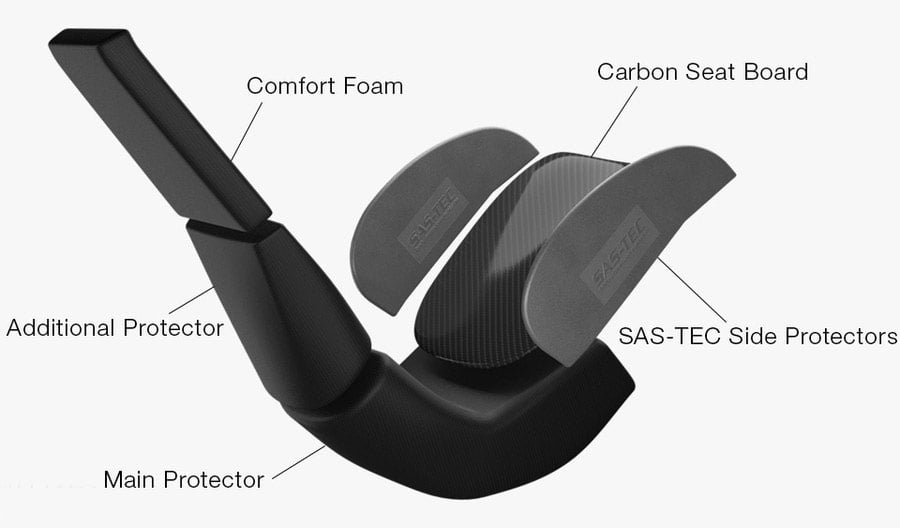

This is usually included in modern harnesses by means of a mousse bag (foam), airbag, or a combination.

The mousse bag is the most reliable and complete protection, as it is always present. It is our recommendation for first time buyers, where the risk of launch and landing accidents is perhaps at its highest.

Not all mousse bags are the same, they vary greatly between models and manufacturers. In some cases the protection is only the bare minimum cost-effective solution to pass certification (a small chunk positioned over the test impact point), but there are some like the Advance Success 4 (pictured above) which goes well beyond the minimum spec, having deeper foam than necessary and adding continuous foam behind the back, and on the sides – areas not tested in the EN test, which features a single impact on the lower back region.

The airbag concept provides good impact protection on the first impact, at the most common angle. They are effective on flat landing surfaces (landing fields and launch sites) but not effective if the impact surface has pointy bits. Modern airbag harnesses like the Advance AXESS 3 AIR, Gin Gingo Airlite 2, Kortel Karma II, Sup'Air PIXAIR and Woody Valley Haska 2 have a pre-inflation system that expands the volume of the harness before flight so you have some protection during the initial launch phase. Airbags help to reduce harness weight, especially when incorporated into a reversible design that produces a convertible paragliding harness-rucksack. You must be extra careful not to puncture the bag – easy to do when on rocky launch sites.

(b) Buckles

Recent safety notices on T-lock self-locking buckles means many pilots and manufacturers are aware of the risks posed by mechanical failure. Instances of failure are rare, but it is something to be aware of during your equipment maintenance checks, and particularly when buying an old harness. It’s a critical safety feature because during launch and landing your weight should be supported on your chest-strap, and it can be very alarming if the chest-strap pops open. The benefits of quick-buckles are ease of use and safety (removing the harness in an emergency is fast).

The alternative system is push-through buckles, which have been used since the first paragliding harnesses were invented. They are very reliable, but fiddly to operate, especially with gloves or cold fingers. With a bit of practice, you can develop the knack.

Some harnesses have no buckles and require the pilot to ‘step in’ to the system (kind of like putting on a pair of swimming shorts whilst wearing flippers). This can be extremely awkward. You save a few grams, but acquire a big negative: if you ever need to get out of your harness in a hurry (water, tree, high wind, landing under reserve) you cannot get out. A hook knife is recommended (mostly negating the small saving in weight).

(c) Reserve parachute position

All harnesses except for those designed for school training and mountain ascents will feature a place to stow your reserve parachute: under the seat, at the back, or on the chest.

Front mounted (on the waist-strap) is often considered to be the safest position, from a deployment point of view, as you always check your closure pins (it’s in front of your face), you can see the handle when you’re in trouble, and you can reach it with either hand. However, if your risers become twisted, the reserve can become harder to access.

The reserve strops might run around to shoulder attachment points via a gusset, which is the preferred solution, but in some cases with front mounted reserves (and very often with detachable reserve pouches) the reserve is connected directly onto your main karabiners.

The pros to this are that you ride down in your normal flying position, and if your wing down-planes you are not forced into the dreaded horizontal position. Assuming the pilot has disabled the main wing, shoulder mounted reserves force the pilot into the proper Parachute Landing Fall (PLF) position; with a karabiner-mounted reserve, getting into a PLF position should be as simple as passing one arm around the reserve bridle and standing up. The cons are that should you have a karabiner malfunction in the first place, you are royally skuppered if you haven’t installed the reserve on separate softlinks.

Other aspects to consider with front mounting the reserve is that this can tend to make clipping in and out of the harness more fiddly, unless using a pod harness that has a front reserve container integrated into the speedbag, and having the reserve container dangling in front of you can make things a bit more awkward on the ground, especially if your reserve is bulky and heavy.

A reserve installed under the seat helps the reserve drop away and minimises tangles during deployment. The volume of the reserve container is important, because some harnesses are not designed to accommodate big reserves: some lightweight pods will not accept old large high-volume Pull Down Apexes. This is particularly relevant with underseat reserve containers as they can be compressed by your weight during a high-G manoeuvre, making reserve extraction difficult.

In a few cases, the reserve is stowed on your lower back, which requires a longer strap from handle to reserve or possibly a more awkward handle position.

In the old days, the reserve strops used to run in a gusset with a continuous hook-and-loop fastening strip which liked to fray, grab threads from the reserve shrouds or become bonded and leave the pilot dangling at an odd angle. It’s preferable to get a modern system which uses a zipped gusset. Any part of the reserve system that features large areas of hook-and-loop fastening needs to be regularly pulled apart and lightly secured, to ensure hassle-free release.

(d) Flight deck

Standard upright (non-pod) harnesses do not include a flight deck (cockpit). Flight instruments will need to be mounted using either harness mount, leg mount or flight deck. Pod harnesses do tend to include an integrated flight deck, although the design and size of these varies.

If it has one then what is it really like, in flight? This can be a real irritant when in the air, where it becomes difficult to manipulate objects. Things to watch out for are the angle of the instruments once you’ve loaded on all the things you usually fly with, and whether the chest strap interferes with visibility or the touch-screens. Some flight decks feature a removable top strip (flight panel) which is great for post-flight instrument management.

(e) Stowage

This one is hard to compare without having the harness in your hand, as the dimensions and volumes of the packing spaces are seldom measured. Most harnesses have adequate basic stowage and will take a standard paragliding rucksack, a concertina bag and your lunch. Harnesses designed with bivi flying in mind (e.g. Kortel Kolibri) will have ample room for extra gear; those designed for hike-and-fly racing (Skywalk Xalps) will certainly not.

A very useful stowage area to look out for is the underseat ballast space, which means you can position a big water store or other soft items, in a place that won’t upset your centre of gravity.

Side pockets are particularly useful on a pod harness, and need to be deep with wide zipped access to allow for the awkward nature of in-flight pocket navigation. Pockets in your jacket can be difficult to reach; it’s nice having a pouch for your gloves, sunhat, drinks, snacks, and camera.

(f) Seat board or no seat board?

There’s no simple answer, because although you might try one harness that lacks a seatboard and find it unresponsive, another brand might produce a very different result. The seatboard usually gives you a more rigid surface under your bottom that allows you to feel the movement of the risers in a more direct manner, allowing for more precise weight-shift control. However, unless you are flying a very responsive wing, it’s unlikely to make much difference.

If you find your wing unsettling or you are upgrading to a higher performance class, the seatboardless harness can calm things down and provide a mellower ride.

If you’re not sure, you can get both – designs like the Supair Delight 2 and Supair Strike allow you to remove the seatboard to change from ‘full control’ to the lighter ‘softer’ version.

(g) In-flight adjustment

Although a good harness setting session should help you trim the harness correctly, things are often different in flight – you don a thick winter jacket, you decide to fly in trainers instead of boots, or the harness fabric stretches over a season of endless summer days. At these times its useful to have straps you can easily adjust inflight. The length of the pod can be a tricky one to modify whilst flying, but the lumbar and lateral supports, shoulder straps, and chest strap should be possible. Straps on some ultra-lightweight harnesses have an unpleasant habit of slipping, resulting in you being never-quite-comfortable. It’s up to you to balance your priorities: a comfortable flight, or a comfortable walk out?

(h) Build quality

The quality of fabric and manufacture directly impacts the cost, but not in the way you might think. A harness with more expensive materials and more precise construction can yield a much longer life and higher resale value, which means your real cost (per hours flown) is lower. Your body size is unlikely to change much over time, so it pays to get a harness that really matches your physique, so you can enjoy it for years.

When weight reduction is the priority, things get expensive fast, because specialist materials have to be used. Here again, the cheaper production methods will really suffer in the long term; don’t expect longevity from a race harness made of ripstop and string!

Build quality is difficult to define on a product page or review, and is often revealed only over time. Over the years, Flybubble has built up experience with the various brands and has gravitated towards those with higher production values. As we have most harnesses in stock, you can opt to benefit from a harness fitting session where you can inspect them yourselves and make up your own mind about the quality.

Brought to you by Flybubble

Like what we do? The best way to support us is to buy gear from us and recommend us to others, thank you!