The transition from ridge soaring to thermaling is often led by the experienced pilots, who somehow seem to 'know' when to glide out into the big unknown void of Beyond The Ridge Lift. Whenever you try to follow them, you seem to go down. What do they know? And how do you develop this skill?

Here's a useful place to start. Watch how we work the tandem at Devils Dyke to build up height before going cross country.

“So because I’ve got lift, I don’t need to stay on the slope.”

This is a key skill to develop. It dominates the transition from being a ridge soarer to being a cross country pilot.

If you soar up and down the ridge there will be moments when the lift increases. The average ridge lift might be 0.3 m/s or so, but occasionally there is a little spike above that (followed by a bit of sink). It’s often subtle, just a small increase, but it’s sudden and possibly slightly turbulent. If you look down and can’t identify the obvious terrain feature that explains the lift, then it’s likely you’ve just flown through a thermal.

It’s easy to make the mistake of ‘waiting for the big one’ and soaring up and down, disregarding these weak bumps. But doing so means you’re throwing away hundreds of chances to climb up and away.

Instead, when you encounter a slight spike in lift, turn immediately into wind and fly off the slope. Continue directly upwind until the lift ceases. Then, to make sure you’re not missing out on the real party, continue until you’ve sunk to the minimum height you need to safely return to the ridge lift – the limit of your ‘reach’.

Found nothing? Hurry back to the safe old ridge lift and soar your way back up again.

Repeat that pattern over and over, and you’ll begin to build up experience at how far you can push out from the ridge, and also the feeling of the thermal currents and the gaps between successive thermal cores.

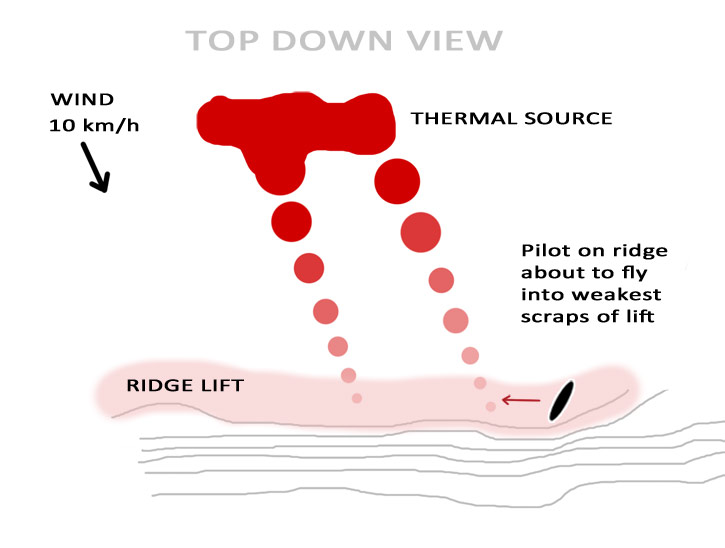

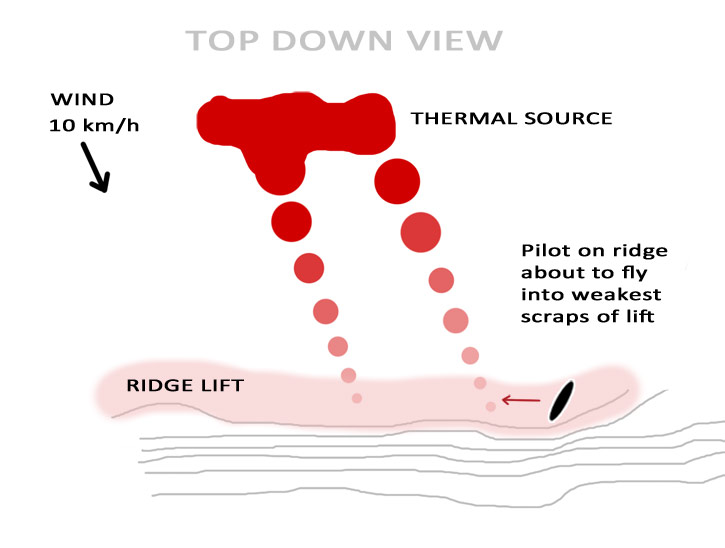

Let’s say there’s a single thermal source somewhere upwind of the ridge. The wind blows over it towards the ridge, and scrapes off all kinds of thermals, strong ones going up in a hurry, and the best biggest ones that power straight up and don’t ever reach the ridge. In fact most of the thermals won’t get to the ridge.

So you see, it’s unlikely that you will hit that boomer if you just soar up and down, hoping for a miracle. All you’ll get is the weaker scraps that don’t have enough energy to escape the wind drift. Not enough to climb in, they just push you back over the ridge near launch.

But they are excellent markers that signal where the thermal must be. They can’t drift sideways, across the wind, they can only go directly downwind. So when you get that scrap, it’s the end of a sniffing trail for you that you can follow to da bomb.

As said in the video “I just glided into wind, in continuous lift, there’s another little beep. I’m just trying to follow the lifty line.” This is the art of sniffing out the pathway of thermals that leads to the real core. Once you can find the better thermals, you’ll be high above the ridge soarers, and well on your way to becoming a cross country pilot.

Brought to you by Flybubble

Like what we do? The best way to thank and support us is to buy gear from us and recommend us. You can also subscribe to Flybubble Patreon. Thank you!